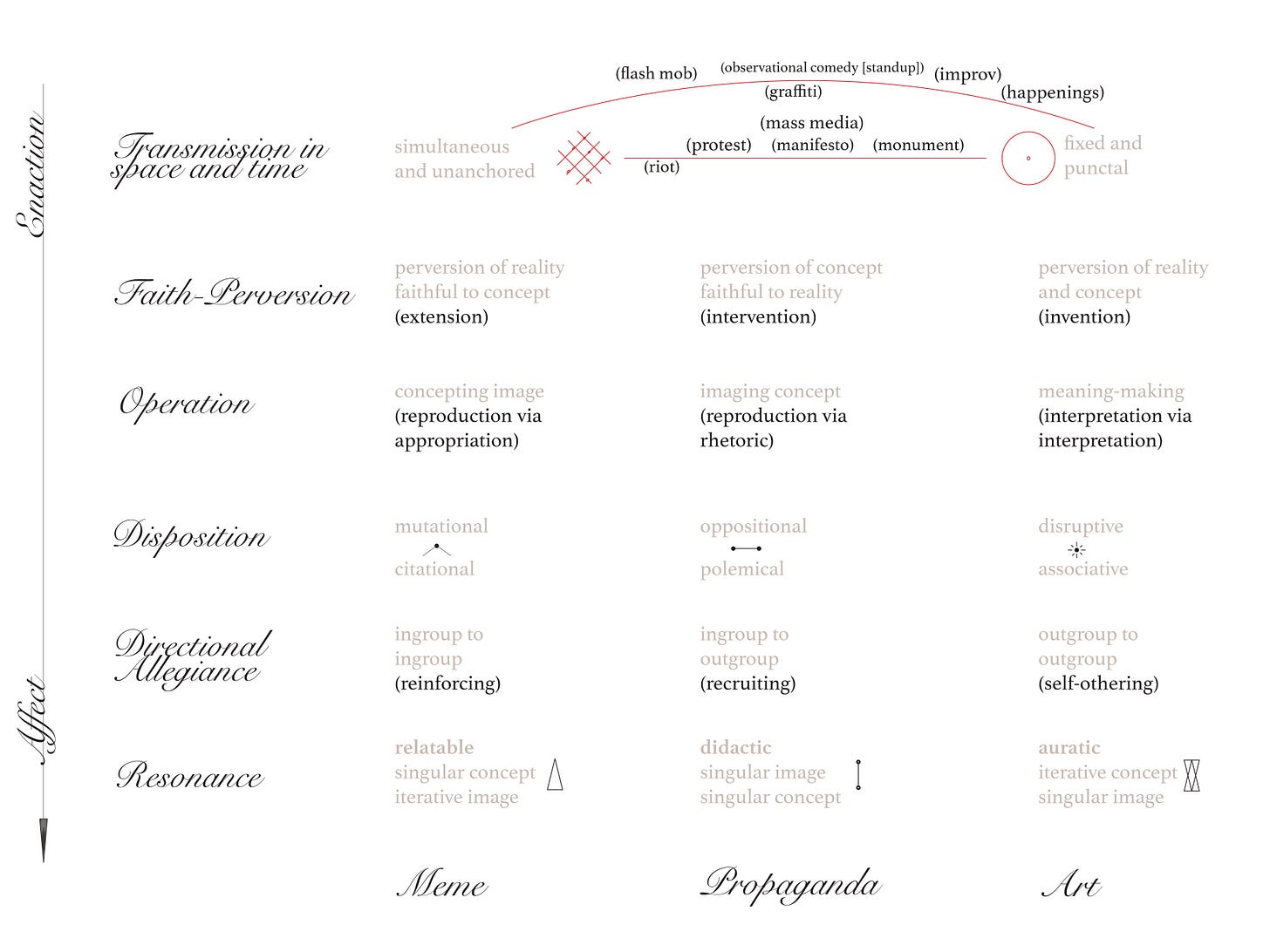

This is an essay that I published as a zine to accompany a work made by Jack Morillo, an artist-friend of mine, earlier this year. The work is reproduced below.

The declarative "Anything can be a meme!" indexes the same conjunction of swaggering free-marketism and naïve transhistorical Enlightenment as "Anything can be art!" with a respectively proportionate emphasis on the former or on the latter. The way in which free-marketism goosesteps about town as the heir of Enlightenment (legitimate or bastard, as determined by mood) is also reflected in the relation between memetic and aesthetic practice: the content or material of both is essentially the same (i.e. potentially anything), but the explicit or implicit pronouncement of a given anything as one or the other gives it a broad yet readily acknowledgable social form. There are several axes by which one might compare and contrast the social form a meme or a work of art prescribes; a speculative map such as Morillo's is not to be contested on the ground of one nitpicked counterexample or another, but rather on the antinomies proposed and their capacity for interrelation. A weak or missing line better affords critique than the assumptive generalizations that serve as its nodes—not because either is more important than the other, but because starting with the former organically produces reconstitutions in the latter, whereas the inverse seldom ever gets to cutting with the knives it sharpens (more out of nervous habit than concrete intention).

What follows in the case of Meme/Art/Propaganda is that the central nodes will bear the most weight—the highest density of lines. Propaganda, in addition to being the least generic and most skewed in valence of the three principal axes at play here, renders something of the archaic to the same degree that the meme renders the New: "Is propaganda art?" feels more passé than "Are memes art?" although both are heavy-duty eye-rollers. But the qualitative distinction between the two is clarified by a different pair of questions: "Is this mere propaganda?" vs. "Is this just a meme?" The negative pole of the former is "...or is it art?" while the latter's is "...or is it for real?" Of course, one always has doubts or convictions about the "reality" (truth value) of propaganda, but these are not the primary subject of interrogation, which is instead how its material is represented—"bad propaganda" is crude, overbearing, or otherwise falsely immediate representation that contrasts with "works that communicate and instruct artfully" (that is, good pedagogy).

Propaganda, then, is an eminently aesthetic form—a dogged sussing out of the Good and the Bad whose object is the work of propaganda. Memes, despite comparable anonymity of authorial production, typically rely far more on a subjective deixis: a meme urges us to read the person who uses it as much as the meme itself. This gives memes a significant ethical charge, where "Is this just a meme or is it for real?" ("...how you really feel?") is a habeas corpus addressed to the contemporary subject that cuts straight to the normative heart of affect in all its aspects (genesis, representation, performance, etc). Of course, as demonstrated with 4chan and the rise of the alt-right last decade, the unanswerability of this query is itself inextricable from memetic practice in its purest form—i.e. irony as the naked triumph of exchange value above all else; a total rejection of classical ethics and the classical subject that yields their fullest apotheosis, in which we are somehow past the naïveté of the Good Life yet remain compelled to speculatively taxonomize ourselves to a degree that would make any colonial administrator or phrenologist blush. God may be dead, but the dialectic of Enlightenment is surely alive.

In keeping with traditions of pop culture analysis set by the previous century, memes are simultaneously the semiotician's wet dream and the critical theorist's nightmare. But, whether with enthusiasm or with dejection, both points of view acknowledge that memes demand to be read aesthetically, even if this belies their truth, because they perform the essentially aesthetic function of concentrating normal experience into a playing field that enables conscious engagement. If art has been the privileged site for investigating the relation between the aesthetic and the ethical since time immemorial, it is in this sense above all that memes fall under the domain of aesthetic theory and practice.

~ ~ ~

The central positioning of propaganda in Meme/Art/Propaganda requires it to act as mediator between the memetic and the aesthetic. The title is M/A/P (rather than the column order M/P/A) because of an implied sequence: thesis-antithesis-synthesis. As stated above, propaganda is arguably the narrowest concept of the three in terms of usage. By being made to define itself point by point against the other two, the possibility of a more general (and more generous) propaganda-concept opens up. This makes the middle column the most subject to contention and revision by the reader, but only because it is the zone least encroached upon by overdeterminations. To better delimit a space for critical engagement with M/A/P's proposal of propaganda as dialectical synthesis, I want to make two basic observations about how the work of propaganda differs from the meme and the work of art:

1. Propaganda is not content-agnostic the way memes and art are. It does not abjure content in favor of form nor dismiss the content-form distinction as imaginary or ideological—it posits the relation between form and content as inextricable and dialectical. Anything can be art (given the proper context); anything can be (the material for a) meme. Not anything can be propaganda—which is to say that nothing can be propaganda without a specific dialogical conjoinment of author and reader. Propaganda is no more or less a social form than memes or art are, but it renders its sociality explicit and has no illusions of form as radically autonomous.

2. Propaganda asserts a dialectical entwinement of the aesthetic and the ethical; unlike the memetic and aesthetic comportment, it does not delude itself into thinking that their relations are laissez-faire. I described earlier how the assessment of propaganda is primarily an aesthetic rather than a veridical judgment. But this is because in propaganda, truth is not a question of mere veridicity or "truth value." The truth of propaganda is instead an immanent ethical injunction arising from an aesthetic practice that is able to sharpen a contradiction between truth values whose resolution relies upon the reader. The classical contradiction that propaganda rests upon is that between present suffering and future peace, where the unequivocal force of the former and the concrete imperatives subtending the latter come together to produce inexorable collective demands. Ever since capital became the motor force of world history, this contradiction has taken the more specific form of that between the iterativity of class conflict and the potential end of class conflict. A general or universal propaganda-concept would extend its apparatus such as to take any contradiction, however big or small, and not only subject it to scrutiny and contemplation (i.e. aesthetic theory and practice) but also ultimately orient one toward its practical (i.e. ethical) significance.

While these remarks on propaganda are of negative derivation, the meme and the work of art obviously have their discursive place. They are incredibly malleable and motile socio-cultural forms that I have no will (or, more importantly, power) to be for or against, let alone resolve out of existence; the many contradictions both within and without my characterizations of them above provide ample testament to this. But most take the discursive legitimacy of memes and art as a given. Meme/Art/Propaganda, in its scrupulous attempt to map its relations in a way that irons out the affective wrinkles of their usage to reveal their conceptual affinities, ought to compel the reader to try this exercise for themself.